The aim of this project was to transform the online display of a fascinating portrait collection of over 16,000 images by analysing each derivative and choosing the ‘best’ one.

One of the most captivating collections that I have worked with at Imperial War Museums has been the Bond of Sacrifice collection. Started before the museum was even founded, and before the end of the First World War, the collection aimed to bring together a set portraits, often submitted by close family members, to commemorate those who had served.

Objective and methodology

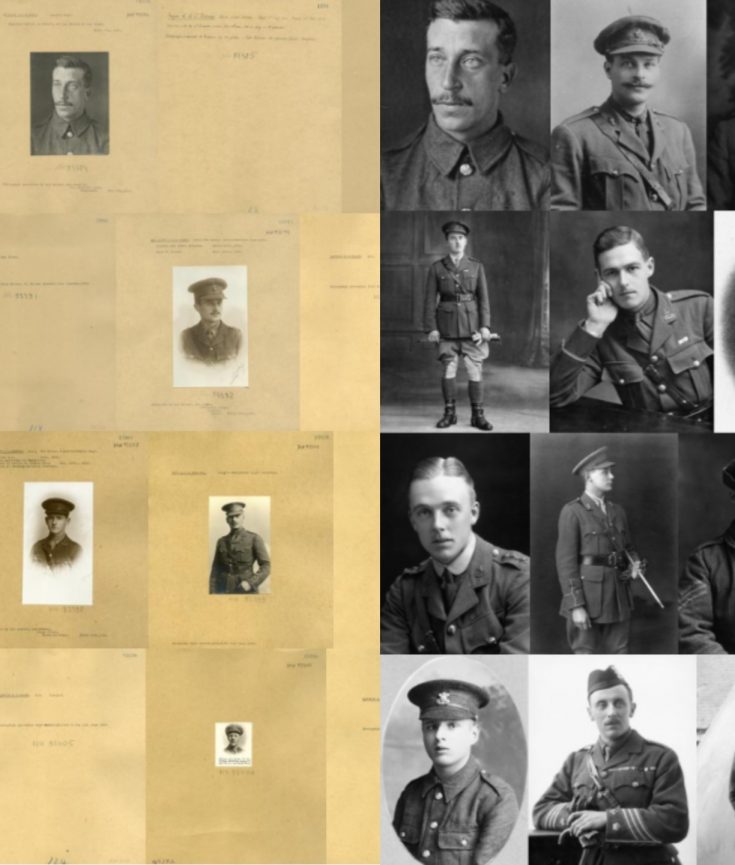

The issue with the online display of these records is that each record often had two or more images and often the one that got displayed was the reverse, or a small mounted image surrounded by empty space. In total there were over 35,000 image files so doing anything manually was out of the question. Instead I wrote a very simple script to push them all through the Google Vision API – specifically the facial recognition method – and analyse and store the results. The data that comes back is fascinating – firstly of course it tells you whether it has detected any faces at all. Then for each you then get a very rich set of metadata that locates facial features on the image and gives pixel coordinates, and it transforms those into measure of three dimensional angle. Finally, there are some more subjective assessments of the image such as the presence of headware (very useful for military hats!), the expression on the face based on a rating of ‘happiness’, ‘surprise’, ‘sorrow’ and ‘anger’ (which you would think would be useful, but actually proved disappointing), and some more technical measures such as ‘blurred’ and ‘under-exposed’ (I like to think it’s a testament to the quality of this collection that none of the images were identified as either).

Practical application

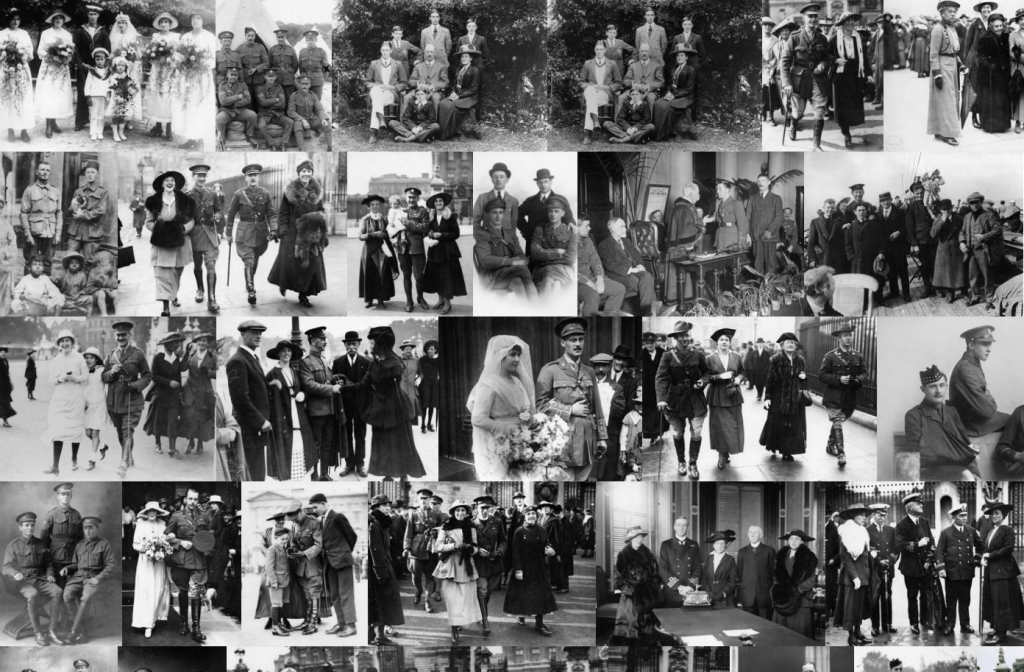

With API responses for every single image I was then able to look at the data for any given record and determine which one had the ‘largest’ face – simple as that! The other thing was I could detect which images had no recorded faces and were therefore likely the reverses, and assign a rank in the form of ‘biggest face’ 2, ‘face but not biggest’=1, ‘no face’=0 and feed this into our collections data as a sort parameter. The end result can be seen in this composite before and after demonstration and any user who visits this collection on the Imperial War Museum site will now have a much richer experience.

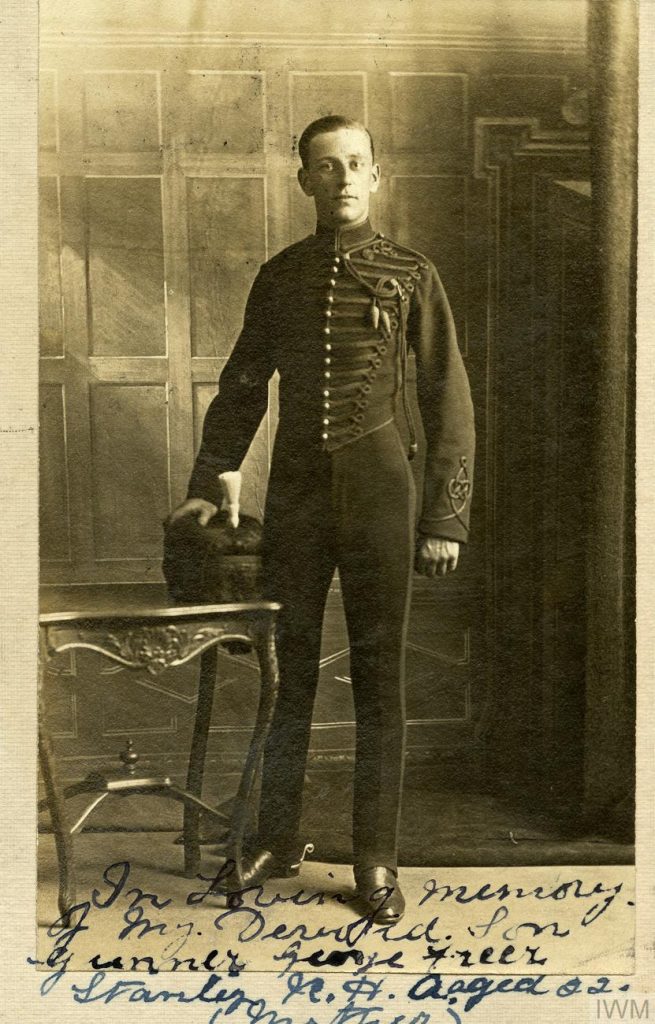

There’s a lovely side story to this work too. In the IWM collections there is a wonderful image of the Bond of Sacrifice collection stacked up on tables from when it arrived, ready to be sorted. Someone had taken the trouble to lay out a few example images and we knew those images ought to be in the collection. But hunting for each image amongst over 16,000, and especially when they didn’t always show the portrait in a search (until we fixed the sort order) really was hunting for a needle in a haystack.

But one image was notable in that it was a full length portrait, less common in the collection. Using the face detection data I was able to identify those images which had smaller faces located towards the top of the image – something that would characterise these – and narrow it down to under 1,000. With them all displayed it proved easy to pick out our elusive image.

Experiments

The sheer quantity and quality of the data allowed for some other, less practical and more playful, experiments. With each of these examples click on the image to be taken to a live demonstration.

Great items from you, man. I’ve take into account your stuff

previous to and you are simply extremely

fantastic. I actually like what you have acquired here,

certainly like what you’re saying and the way in which wherein you assert it.

You’re making it enjoyable and you continue to take care of to keep it wise.

I can not wait to learn far more from you.

That is actually a terrific web site.

WOW just what I was searching for. Came here by searching for ira eligible precious metals

As?ing questions are truly pleas?nnt thing if you arre not

understanding somkething totally, but t?is p?st provides good understanding ?ven.

Hello. fantastic job. I did not imagine this. This is a splendid story.

Thanks!

?y spouse aand I srumbled oer here by a different web address and thought ? should check things out.

I like what I see so now i’m following you. Look forward to looking into your web page repeated?y.

Pretty! T?is has been an extremely wonderful post. Thanks foor

providing this information.

?f you desire to increase your knowledge just keep visiting this site and be ?p?ated

with the most recent gossip poste? here.

F?rst of all I wlu?d like to say aw?some blog!

I had a quick question that ?’d like to ask if you don’t

mind. I was ?nterest?d to know how y?uu center yourself annd cleaqr your head before writing.

I have had a difficult time clearing my mind in getting my ideas

out. ? do take pleasure in writing however it just s?em? like the first 10 to

15 m?nutes are generally wasteed just trying to figure out ho? to begin.

Anny su?gestikns o? tips? Appreciate it!

Este modelo além de ser extremamente resistente, permite economia ao pecuarista, evitando desperdício na

alimentação do gado. https://Flora-lis-Barros.technetbloggers.de/caixa-d-c3-81gua-tubular-a-solu-c3-a7-c3-a3o-ideal-para-armazenamento-eficiente-e-sustent-c3-a1vel

Greetings! ?ery helpful advice in th?s p?rticular post!

?t is th? littl? ?hanges that m?ke the most important changes.

Th?nks for sharing!

awesome